A Pillar of Ford

Automobile

August 2000

David E. Davis, Jr.

courtesy and copyright of Automobile

http://automobilemag.com

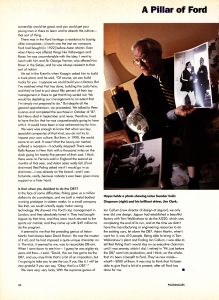

From public relations supremo at Ford to chairman of Aston Martin, Walter Hayes has seen it all. Story by David E. Davis, Jr. Photography by Tim Andrew

Walton-on-Thames, England

Walter Hayes was about to celebrate his seventy-sixth birthday when I interviewed him at his home, Battlecrease Hall, in the village of Walton-on-Thames. The house, its garden, and the surrounding village conform to American visions of what retirement in England might be like, but despite its lush green beauty and unsullied views of one of the western world’s great rivers, Walton-on-Thames has been overtaken by the suburban sprawl that surges out from London’s Heathrow airport.

Nothing about the interior of the house hints at Hayes’s remarkable career with the Ford Motor Company, his deep involvement with Ford’s motorsport programs, his almost single-handed rescue of Aston Martin, or – for that matter – his long friendship with Henry Ford II. The rooms are bright and comfortable, nice old paintings grace the walls, and Elizabeth Hayes’s very British collection of Staffordshire figurines fills a set of front-room shelves.

Hayes is a perennially cheery man of medium height and build. Wearing a navy blazer and striped tie, fiddles with a pipe and a pair of eyeglasses. (After some years of deteriorating eyesight, he will celebrate this birthday by having microsurgery on both eyes).

Hayes should have considered a writing career. He writes awfully well and has two very good books to his credit: the definitive (and authorized) biography Henry: A Life of Henry Ford II, published in 1990, and, more recently, an elegant little book about a series of events in the aftermath of the Bounty mutiny. It is called The Captain from Nantucket and the Mutiny on the Bounty, and it recounts the travails and adventures of a Nantucket sea captain who actually stumbled onto the last survivor of the Bounty mutineers at Pitcairn Island while on a seal-hunting voyage. The book is available from the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan, and the price is $100.

Hayes joined Ford in Great Britain in 1961, after several years in the newspaper business. He was associate editor of the London Daily Mail and was trying to improve its readership among women, which led him to hire Penelope Mortimer-novelist and wife of John Mortimer, author of the Rumpole series – to create an advice-to-the-lovelorn column. He was called to a meeting with proprietor Lord Rothermere, who said, “That woman. In her first article she used the word menopause, and I’m not going to have words like that in my paper.” Walter held a council of war with his wife, decided that Fleet Street might never catch up with contemporary culture, and abandoned his newspaper career.

Sir Patrick Hennessy, Ford’s British chairman, learned that Hayes was at liberty and asked him to join Ford as a sort of free-ranging head of corporate communications, with the additional sweetener of an offer to put him on the board in six months “If things worked out”. Ford and Hayes were a great marriage, and Hayes’s career at the Ford Motor Company was brilliant indeed. He retired as Vice chairman of Ford of Europe in 1989 and promptly became chairman of Aston Martin, where he spearheaded the creation of the DB7. Following his retirement in 1994, he was named life president of Aston Martin, a title that continues to give him great pleasure.

Were you a car enthusiast before you joined the Ford Motor Company?

Well, I was interested in cars, but what really happened was that I was editing a paper called the Sunday Dispatch in the early Fifties, and I wanted a new, lively motoring writer who wasn’t just some Joe. I wanted somebody new, so I hired Colin Chapman, almost before he’d started Lotus. He was a great mentor of mine, and I really learned a lot from him. People should understand that Colin was never a great engineer, but he was a great engineering idea man. He’d draw the car, then draw a box and mark it “engine”. It was Colin who perfected this mid-engine layout in racing cars. He had so many good ideas that he would frequently leave one perfectly good one to get on to the next.

When I first met you, you had come to New York to accept an award for the Lotus Cortina…

Yes. In 1965. Best sports sedan, by Car and Driver.

And your fingerprints were all over that car.

Well, not entirely. I joined Ford in 1961, and the Cortina was well underway. One of the first things Patrick Hennessy showed me was the Cortina prototype. It wasn’t until the Cortina GT came along that I was really involved. I’ve gotten too much credit, when what I did, really, was to pick good people to work with, abd the real story is different. The real story has to do with the postwar baby boom, and I just happened to be there.

The postwar baby boom in the United States is the most significant influence on culture and economics that the world has ever known. In 1945, there were more than 2.7 million babies born in the United States. So there were all these young people, and what they wanted was cars. They didn’t want to be kings. Their idea of a throne was a bucket seat. Excitement was delineated in cubic inches. That’s what the world was about.

But in 1957, the Automobile Manufacturers Association had done this ludicrous thing [adopted a resolution not to go racing]. And then, in 1961, when Lee Iacocca was thirty-seven and just appointed vice president of Ford, Don Frey and all those young men sat down with him and pointed out that all these baby boomers were longing for exciting cars, yet this stupid prohibition was absolutely inhibiting our ability to say that we were not building, dull, boring cars. So it was in June of ’62 – just before we launched the Cortina, by coincidence – that Henry Ford II issued the declaration in which basically he said, “We believe that we are better able to judge what is the best way for us to develop cars,” and everything changed.

First of all Carroll Shelby, a great sports car man, was back from his victory at Le Mans in ’59, full of beans. He said, “We ought to put an American V-8 into a European sports car, and I reckon we ought to use a car like the Aston Martin that I won Le Mans with”. He came over to talk to David Brown, then boss of Aston Martin, about it, and David really wasn’t too sure – he later said he thought that was a mistake. So in ’62, Shelby put a Ford V-8 into an AC, and we had the Shelby Cobra.

Then, along came the new Falcon, and guess what, I get a call: “We think we’d like to run a team at the Monte Carlo Rally”. Those huge cars came over and had a class win the first time out, which was astounding.

In ’63, they decided to do the GT40. You know, the dates are astonishing. John Wyer [Aston Martin team manager] was singed up in July. The prototype was on the stand at the New York motor show in ’64. It didn’t do well at Le Mans in June that year, yet it ran thirteen hours. After that, it began winning, and it just went on until ’69.

Then of course, there was Indy. Colin Chapman of Lotus went over in ’62. The following year, Jimmy Clark damned near won [in a Lotus-Ford] but for the yellow-flag business. [Unfamiliar with Indy’s rules for passing when under a yellow flag, Clark lost valuable time while chasing Parnelli Jones and was forced to settle for second place]. Clark, again in a Ford-powered Lotus, finally won in 1965.

Within this great, sort of swelling of “Total Performance”, as we began to call it, we won world championship rallies with Escorts and Cortinas, we invented Formula Ford, and we did the Cosworth DFV engine which won the first time out in ’67! The engine went on to power more than 150 grand prix winners – a record.

If you look at what the Ford Motor Company did by speaking to the young people in the universe, 1962 to 1968 are six years that shook the world! If you look at racing before that time, it was insular. We could have done all the racing in the world in the thirties, and it wouldn’t have made any difference. But in the sixties it worked! Ken Tyrell says that what Ford did in those six years established motorsport as we know it today, and I really think its hard not to agree. It was the Americans who brought commercialism to grand prix racing.

Was that a good thing or a bad thing?

It was an inevitable thing.

Tell me about Aston Martin, and the DB7.

I went down to the Mille Miglia, the retrospective, with the Aston Martin people in 1987. I knew Aston Martin quite well because of Ford’s long association with John Wyer, and I also knew David Brown. Aston’s chairman at the time, Victor Gauntlett, was also there, as was Prince Michael, and they were driving old Astons in the Mille. As we talked, it became obvious to me that Aston Martin was going to be in very serious trouble. Gauntlett made it clear that the cost of meeting emissions and all the other regulations really was making it untenable for the specialist carmakers to continue, and if they didn’t get some kind of help, they’d die.

They had a Volante down there, and Prince Michael drove me to the airport in it. Prince Michael said, “You know, Ford ought to buy that company’” and everybody was laughing. But at this time, Henry Ford II was in his sixty-ninth year, living in England. You know, he’d always loved England, and after his executive retirement, he was spending six or seven months a year here. He had an absolutely beautiful house down near Henley, and he didn’t have much to do. I was also sliding toward retirement myself, and I used to go down there and have coffee with him. I went down there after the Mille Miglia. He said, “What should we do today?” and I said, “Well, you could always buy Aston Martin”.

He laughed and said, “That’s very funny. I’ve been shooting with Peter Livanos [whose family owned Aston Martin], and he has told me quite earnestly that they can’t go on the way they are, and I’ve been thinking about the same thing myself”.

Then he called Alex Trotman, who was chairman of Ford Europe at that time, and I think he called his son, Edsel, and Allan Gilmour [then Ford CFO and executive vice president], and he said, “We’re sitting here talking about buying Aston Martin”.

There was some sense in it for him. All of his life, he’d been frustrated by the inability of his own company to build anything in small volume. If he said, “Why cant we build a thousand of those?” they would say, “We’ll build you 400,00, Mr. Ford, but a thousand? We really can’t do it”. He always thought that these small companies had something to contribute to Ford, that ownership would be good, and you could get your young men in there to learn and to absorb the culture- that sort of thing.

There was in the Ford heritage a resistance to buying other companies – Lincoln was the last car company Ford had bought [in 1922] before Aston Martin. Even when Henry was offered things like Volkswagen and Rover, he was uncomfortable with the idea. I went to lunch with him and Sir George Farmer, who offered him Rover in the Sixties, and he was always resistant to that sort of notion.

He sat in the Kremlin when Kosygin asked him to build a truck plant, and he said, “Of course, we can build trucks for you. I suppose we could build you a factory. But I’ve watched what Fiat has done, building Lada here, and they’ve had to put about fifty percent of their top management in there to get that thing sorted out. We would be depleting our management to an extent that I’m simply not prepared to do”. But despite all the general apprehension, we proceeded. We talked to Peter Livanos and completed purchase in October of ’87. But Henry died in September and never, therefore, lived to have the fun that he was unquestionably going to have with it. It would have been a nice retirement toy for him.

We were wise enough to know that when you buy specialist companies of that kind, you do not try to impose your own culture. But then, in 1990, the world came to an end. It wasn’t that the luxury-car market suffered a recession – it actually stopped! There were Rolls-Royces in New York with a thousand miles on the clock going for twenty-five percent of their cost. I think there were no Ferraris sold in England the second six months of that year, and Aston sales really fell. [Ford chairman] Red Poling asked me if I would go in as chairman – I was already on the board – and I was fortunate, really, because nobody’s ever been given more support or a freer hand.

Is that when you decided to do the DB7?

In the face of some difficulties, Poling gave us a million dollars to do a prototype, and we build a metal-bodied running prototype in sixteen weeks. In a small company like that, we could virtually apply motor racing technology. We showed it to Ford’s top management in London, and they absolutely loved it. They had bought Jaguar by that time, and they were much attuned to the sports car market, and they came up with $49 million to do the program.

It seemed to me that the presiding genius of Aston Martin had always been David Brown. He was the master of it all, and he had imposed a quite unique character on it. The trick, it seemed to me, was to resuscitate DB-ism. When I went down to see him – I guess he was eighty-six years old then – I said, “David, this car has got to be the DB7, and you may think that’s a bit of an imposition, but I’m going to take you to see the car. If you like it, I will be very grateful if you can say, ‘Okay, that is a DB7’”.

We were very lucky. With the supreme genius of Ian Callum [now director of design at Jaguar], we only ever did one design. Jaguar had established a beautiful factory with Tom Walkinshaw to do the XJ220, which was completing the end of its run, and at the time we didn’t have the manufacturing or engineering resources to do the existing cars, let alone the DB7. Aston Martin, when I went for it, was 410 people. Being able to bring in Tom Walkinshaw’s plant and finding Ian Callum, I was able to tell Red Poling that I would stay on as executive chairman until I was seventy, which I did. I retired in ’94, just before the DB7 went into production, and I think, on the whole, that it’s been a benefit to Ford. They’ve now made – what? – 3000 of them. It was nice to think that I’d been able to give Ford a bit of a present, after all Ford has done for me.