Walter Hayes (1924 – 2000) Part 1

Classic Ford

March 2001

Graham Robson

courtesy and copyright of classicford

classicfordmag.co.uk

Walter Hayes, one of Ford’s great visionaries, died on December 26, 2000. This two-part feature is a celebration of his 40 amazing years at Ford.

Although he retired from Ford – officially, but reluctantly – in 1989, he rarely missed an opportunity to meet up with his old colleagues. Whenever there was need of wise counsel about Ford’s past, he was consulted – and there was no better dinner companion in the whole world.

I knew him well, and counted him as a friend, so I know that he would not want to be remembered in a gloomy obituary. This, then, is a celebration, of just a few things he achieved at Ford in forty years :

‘I knew nothing about motorsport when I joined Ford,’ Walter Hayes once told me. ‘Except that I’d hired Colin Chapman to write about cars for one of my newspapers, I was a complete novice.’

Maybe – but he certainly learned – fast. Who but Hayes could have transformed Ford’s public and motorsporting images, could have persuaded its management to back the Lotus-Cortina, could have eased the company in Formula 1, got the entire Rallye Sport programme approved, and made the Escort into the world’s most successful rally car ?

If not Walter Hayes, you might say, someone else would have done the same ? Absolutely not. Not according to Sir Terence Beckett (who became Chairman and Managing Director in that period). Not according to Stuart Turner (Ford’s most famous Director of Motor Sport). And not according to Henry Ford II himself, who made Hayes his closest British confidante.

You have to remember just how different a company Ford-UK actually was before Hayes arrived. A big company, sure. A profitable company, definitely. But with a sporting image – certainly not.

Although the Zephyr had won the Monte, the RAC and the Safari rallies by that time, even in 1960 Ford-UK’s image was down in the dumps. Yet by 1970 there was glamour all around. In 1960 Ford was barely involved in motorsport, but by 1970 Ford was winning everywhere. The last side-valve engined British Fords were made in 1959, yet the first 16-valve twin-cams were on sale by 1970.

This was a complete transformation, not only of engineering, but of image. On the back of this, Ford-UK’s market share surged ahead: by the mid-1970s Ford was Britain’s best-selling car, and has never lost that lead.

In, around, and behind this transformation was a small, dynamic, dapper but utterly persuasive character call Walter Hayes. These days, for sure, we would call him a fixer, a wheeler-dealer, or a spin-doctor. No matter what the launch, the bright idea, the motorsport programme or merely a publicity wheeze, Walter Hayes was behind it.

The important word, though, was ‘behind’ – for although Britain’s entire motoring world soon came to respect Hayes, the general public rarely knew what was going on. It tells us much that, after he died, no immediate obituary appeared in the heavyweight daily press – they didn’t think he was important, but we did.

Yet it was Hayes, the seasoned newspaperman, who inspired Ford’s radical change of image, its surge into world-class motorsport, and its re-invention as a trendy car. Even Ford, who don’t like to promote personalities at the expense of the ‘team effort’ image, now recognise this.

Ford needed someone like Hayes – but they didn’t know him at the time. London-born Hayes had started his working life as a junior reporter on the Daily Graphic newspaper, then spent the war years in the Royal Air Force.

[In later years, when happily puffing on the ever-present pipe, he used to tell the story of his first Board Meeting at Ford-of-Europe in Cologne, when a very formal German politely enquired if he knew much about the city:

‘Oh certainly,’ Walter cheerfully replied, ‘I often flew over it – in 1944 !’]

Afterwards, he rose to great heights on the Daily Mail, and the Sunday Dispatch, before he attracted the attention of Ford-UK’s chairman, Sir Patrick Hennessy. It was typical of Walter, who missed no opportunity to socialise, that he had first met Sir Patrick at the lunch table of the Daily Express proprietor, Lord Beaverbrook.

Sir Patrick, the charismatic Irishman who had been running Ford since 1939, knew that the company needed a boost. Even though Ford dogged Austin and Morris for sales leadership, the cars’ engineering and styling was controlled from the USA, and Ford-UK would not get engineering control until the 1950s.

But the sleeping giant was stirring. By 1960 the first of the new-generation engines – the Anglia’s 105E, a small, high-revving little ‘four’ which Cosworth would soon turn into a successful little racing unit – had appeared, and work on the very first Cortina had already started. To line up with new products like these, Sir Patrick knew that he needed a new approach to Ford-UK’s image.

Enter Walter Hayes, ready to leave the newspaper industry, already a good friend of Sir Patrick, with a dynamic personality and a head full of great ideas:

‘Sir Patrick needed to bring some outside thinking into Ford,’ Hayes once told me,’ but there really wasn’t any such thing as Public Relations in those days, and no-one seemed to know much about it. We agreed that I should join him to run “Public Affairs”, and if everything worked out I would then become a Director.’

Hayes moved into Dagenham in the winter of 1961/1962, at the same time as Dearborn embraced its new Total Performance philsophy. Bright ideas, and a new approach to performance motoring, was needed.

It was typical of Hennessy, by the way, that Hayes arrived without fanfare, and without explanation:

‘Suddenly, there was this little man in an office of his own, behind a typewriter’, long-time PR colleague Harry Calton recalls, ‘working away behind an open door. Nobody knew who he was at first – but we soon learned….’

Although he was not then a motor racing expert, Hayes already knew the right sort of people. Having employed the brilliant engineer Colin Chapman, of Lotus, on the Sunday Dispatch [‘but he was hopeless at meeting deadlines ….’], he soon turned to Chapman with an exciting proposal, and dined out for years on the story:

‘Colin, I said, why don’t we join forces ? Starting with the Cortina, why don’t you design a new saloon we can go racing with – and why don’t you make them all for us, too….?’

Although it wasn’t as simple as that – it is never simple at Ford, where everything is analysed to death …. the eventual result was the Lotus-Cortina, complete with its Lotus twin-cam engine and lightweight panels and casings, a car which won as many races (and, later, rallies) as it infuriated its owners with a lack of reliability, and a car which transformed Ford’s motorsport image. Quite unconceivable to Ford’s old guard, it was the first of many innovative sporting cars inspired by Hayes.

His decision to build a new motorsport HQ at Boreham, in Essex, helped too. Up until then, as he put it: ‘I discovered that motorsport was my responsibility. I soon found that the “works” rally cars had been prepared in the press garage in Brentford, and the team had been for “gentlemen and our dealers”. Some of our rivals were much more serious, so I had to change all that.’

Changing that, included hiring Syd Henson to run the team, digging deep to find £32,000 to build the new Boreham Motorsport centre, which opened in mid-1963, and re-arranging the management succession:

‘Henson hired Pat Moss, which was right, but he was a difficult character. He was always threatening to resign. One day he came in, complaining about something, and I said : “Syd, I’ve decided to accept one of your resignations ….” – and I appointed Alan Platt instead,’

Throughout the 1960s, and gleefully publicised by Hayes’ new squad of PR men, Ford-UK fizzed with new ideas, new models, and an ever-growing involvement in motorsport. If not directly, then always behind the scenes, as a string-puller, impresario, negotiator, advisor or the finder of money, Hayes was an ever present.

These were the days when Cortinas were taken to the Italian resort of Cortina, and run down the famous ski slope, when F1 champion Jim Clark was persuaded to drive Lotus-Cortinas in the racing British Saloon Car Championship and when Ford build well-placarded but quite impractical electric-powered town cars. It was also a time when more and more show business personalities started to drive big Fords, all provided for free by the publicity-conscious Hayes.

This was the time, too, when Hayes acted as a mid-wife for so many sporting projects – in bringing the Ford GT racing sports car project to Le Mans (and the production lines to Slough), in drawing Cosworth Engineering closer and closer to Ford, and eventually in making sure that Ford, Lotus and Cosworth were linked in a Formula 1 race programme:

‘Colin Chapman sold us the idea around his dinner table, and Keith Duckworth didn’t seem at all worried about the task. So Harley Copp (Ford-UK’s technical director) and I went to a Board meeting in 1965, and under “Any other Business”, I piped up and said:

“Harley I would like to a Grand Prix engine.”

‘Later I had to “sell” the idea to Henry Ford II in Detroit. He wanted to know what such an engine would do for us ? I said : “Well, in my opinion it will win some Grands Prix, and I also think it will win a World Championship.”

– which has to be the biggest understatement of all time !

Yet Hayes insisted that he had not always been a motor racing fanatic (‘I was surprised how much we could do with little money in the early days’), but by the mid-1960s he certainly knew more about his subject than anyone else at Ford-UK.

It was Hayes who tapped Alan Mann, previously a little-known club racer, to make it possible for the Lotus-Cortina to win the European Touring Car Championship, Hayes who inspired FAVO to make sense out of the muddled Ford GT Le Mans development process, and who made sure that Ford-based engines were involved (and winning !) at every level from Formula Junior to F1, in saloon cars, sports cars, and single-seaters.

There were stunts galore. Sending Eric Jackson and Ken Chambers to beat the London – Cape Town record in a Cortina in 1963 was one thing (‘I got fined by the Stewards of the RAC for that – they said it was encouraging racing on public roads’), but asking a team of enthusiasts to break endurance records at Monza in a Transit van was another. It was all very well for the Jackson/ Chambers duo to drive round the world in a Corsair, but to race back from Cape Town to Southampton against an ocean liner was quite another !

Yet this was the right time, the Swinging Sixties when everything seemed to be possible, and in many ways Ford’s new 1960s models made his job easier. The Cortina, selling 250,000 cars every year, was soon a world-wide success, the first of the Escorts made a similar impact, and in 1969 the new Capri became ‘The Car You Always Promised Yourself’.

‘Walter changed the way people thought about us,’ Calton relates. ‘He was the first to get mums, dads and children in our press pictures, doing family things. That was new.’

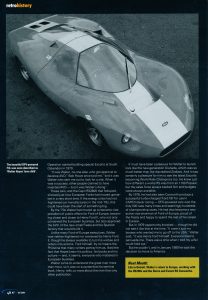

But Hayes had even more innovation in mind. Others may have worked up the nuts-and-bolts, but it was his advocacy, and his behind-the-scenes lobbying, which made sure that the new Advanced Vehicle Operation – the ‘factory-within-a-factory’ – started building special Escorts at South Ockendon in 1970.

‘It was Walter, no-one else, who got approval to develop AVO,’ Bob Howe once told me, ‘ and it was Walter who sent me out to look for a site. When it was a success, other people claimed to have invented AVO – but it was Walter’s doing.’

These cars, and the Capri RS2600 which followed, showed just how European Fords had moved upmarket in a very short time. If the Energy Crisis had not frightened Ford (and other car makers) into their shells in the mid-1970s, this could have been the start of something big.

By the 1970s Hayes, his reputation glowing as never before, had moved up to become Vice-President, Public Affairs, Ford-of-Europe, becoming closer and closer to Henry Ford II, who had not only conceived the European business, but had also approved the birth of the new small Fiesta and the Spanish factory which would build it.

Unlike most other Ford-of-Europe executives, Hayes was neither frightened nor overawed by Henry Ford II, though he always available to turn HFII’s wishes and orders into actions. Ford himself, by no means the philistine that many other writers make him, liked the fact that Hayes knew his politics, his books, and his culture – and, it seems, everyone who mattered in European business.

Hayes, in his own way, came to understand the great man more than most, and to appreciate what he had achieved, so it was no surprise that his seminal book Henry (published in 1990 after Henry Ford had died) tells us more about the man than any other publication.

Not even the Energy Crisis, which caused the AVO operation to be closed down, and caused Ford-of-Europe to concentrate more on bread-and-butter cars than on sporting machinery, could deflate Hayes for long, as Ford was becoming more and more successful in Europe. Hayes, more than most, realised that to keep Motorsport alkive, one of the centres would have to close and:

‘He was totally straight about everything’, Stuart Turner told me, ‘but I was mighty relieved when he decided to close down Cologne !’

For Hayes it must have been a pleasure to launch cars like the new-generation Granada, which was so much better than the discredited Zodiacs – and it was certainly a pleasure for him to see the latest Escorts becoming World Rally Champions too. He knew just how different a ‘works’ RS was from an 1100 Popular, but the sales force always backed him, and budgets were always available.

By 1976 he had also seen Cosworth produce a successful turbocharged ‘Ford’ V8 for use in CART/Indycar racing – DFX-powered cars won the Indy 500 race many times, and seemingly hundreds of Championship races – he had also become a very active Vice-Chairman of Ford-of-Europe, proud of the Fiesta, and was happy to spend the rest of his career in Europe:

‘It took us four years to work out how to do it with the Fiesta. I believe it was our planning and understanding of the market which made the Fiesta work and make money all the way through ….’

Then, in 1979, opportunity knocked, though he did not see it like that at the time:

‘It wasn’t just my bosses who wanted me to go off to the USA,’ Walter said, ‘it was Henry Ford himself. Everyone tried to persuade me. There was a time when I told my wife I could hold out ….’

But he couldn’t, and in January 1980 he moved to Dearborn.