Walter Hayes (1924 – 2000) Part 2

Classic Ford

April 2001

Graham Robson

courtesy and copyright of classicford

classicfordmag.co.uk

‘I think I must have been half-asleep myself at this time,’ Walter later wrote in Henry, ‘where my own future was concerned.’

Early suggestions that he should become Vice-President, Ford-USA, in Dearborn, were easily deflected. Then it got serious. Ted Mecke, the current title holder, decided to retire early, and no less than Henry Ford II moved in for the kill.

‘He told me that taking over from Mecke made every kind of sense. I said that the problems facing the company in the United States were enormous and needed both competent and instinctive responses. In Europe my reactions were like that: in America I would even have to learn how to spell again ….

‘But Henry wouldn’t let it drop. He started saying “when you come” at every opportunity. I tried to hold out, by Henry kept on nagging, saying he needed me….’

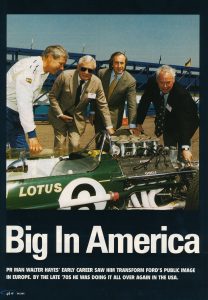

Finally giving in gracefully, he became Ford-USA’s Vice President of Public Affairs in January 1980. For the next four traumatic years which followed the second Energy Crisis (traumatic for Ford, that is, not for Walter Hayes), he re-shaped Ford’s public image, seeing it bounce back from the doldrums.

At this time, it was altogether typical that he chose to live in Ann Arbor, a university neighbourhood, and not in Grosse Pointe, the ‘motor industry ghetto’. As Henry Ford II himself pointed out:

‘McNamara lived in Ann Arbor, and Arjay Miller. All the intellectuals live there. It’s a good place for you….’

It was no coincidence that Walter himself later wrote that:

‘I had shipped three thousand books from England, together with the entire contents of my house, but found too little time for reading.’

It was no coincidence, either, that this also coincided with the period in which Ford-USA’s motorsport programme was revived, with Mike Kranefuss arriving from Europe to manage the process. Mike and Walter got on well – and would do so, again. It was also in the United States that Hayes finally persuaded Keith Duckworth that Cosworth should design a turbocharged F1 engine:

‘I know enough about Keith’, he once told me, ‘to be able to pull his leg, to get him in the right mood. The way to do it was not to go to fancy hotels, but to have him at my home, where my wife could cook him things like toad-in-the-hole, Lancashire hot-pot and other Northern dishes ….

‘Also, at home, we would give him real cups of tea, and offer him as much lager and good British beer as he could drink – after a few glasses of lager, the inspiration really began to flow ….’

And it was Walter, of course, who then raised the much higher investment needed to finance the 1000bhp 1.5-litre V6, and the famous HB normally-aspirated V8s which followed.

Although he charmed the American establishment – as Henry Ford II had sensed he would – the Stateside sojourn lasted only four years, after which Ford needed him back in Europe:

‘We therefore agreed that I would commute between London and Dearborn for the remaining months of Philip Caldwell’s chairmanship, and attend to specific tasks in America as well as those to which I was newly committed on the other side [Europe] of the Atlantic….’

Even while he was in the USA, of course, Hayes missed nothing, his antenna being carefully tuned to what was happening to Ford in Europe. By 1982, with Boreham’s motorsport programme in disarray, he made a fateful phone call :

‘When Walter called,’ Stuart Turner writes in his autobiography Twice Lucky, ‘he told me he was picking up vibrations that all was not well with the RS1700T rally machine …. Would I talk to a few people and write him a note about it ?’

It was typical of Hayes that, from several thousand miles away, he engineered the revolution that got Turner re-installed into the top Motorsport position, all of this a full year before he returned to Europe, as Vice-Chairman, Ford-of-Europe.

Hayes, please note, was already 60 years old, but as spry as ever. Back home once again, he arrived at exactly the right time to see Ford’s sporting and product image reinvented, uncannily taking it back towards that of the 1960s/early 1970s, when almost everything seemed to be possible.

Back in Europe, the Vice-Chairman title meant everything – and nothing – for it had been created especially for him. Although the Chairman, and his President, had much of the executive power, Vice-Chairman Hayes looked after all Public Affairs, Motorsport and sundry marketing matters, and could interest himself in anything else which took his fancy. In particular, he was always Henry Ford II’s sounding board, particularly when HF II bought a house near Henley-on-Thames.

It also gave Walter plenty of time to ponder, and he was good at that :

‘Walter was the great thinker, the great philosopher,’ Stuart Turner says. ‘Throughout the years I worked with him, he refused to get bogged down in detail – there were occasions when I would walk into his office to find him with his feet on the desk, pipe in mouth, just thinking. Some of the get-up-and-go Americans were puzzled by this approach but it was when he was at his best, his most creative.

‘I always envied another of his skills. I would walk into his office, tell him about a particular problem, and he would call on his secretary and dictate an incisive note that struck absolutely to the heart of the problem – and invariably solved it.’

Once installed at Ford, Hayes had become a fearsomely efficient ‘fixer’ – someone who could match ideas to budgets and personalities to personalities – but in those final years he took this skill to a peak. The ‘thinking time’ predominated, and he spent much time prowling the legendary ‘sixth-floor’ at Warley, dropping into an office here, lobbying there, and encouraging somewhere else.

Stuart Turner, originally head-hunted from Castrol by Hayes in 1969 to run Motorsport, became a life-long friend, and often reminded me of his value:

‘If I needed a good word to be put in, to Finance, Marketing, Manufacturing, or whoever, Walter would always provide it – and it usually worked.’

It wasn’t that Hayes had an impressive title (though it was, no question), nor that he went around tub-thumping (not his style) – it was that he was always there, the Wise Owl, to be consulted.

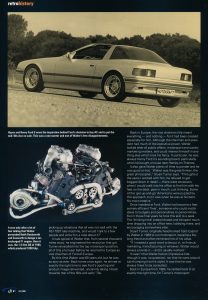

Back in Europe from 1984, he settled back in at exactly the right time, for Turner’s Motorsport renaissance programme was still at its early stages. The time was ripe for important sporty cars like the Sierra RS Cosworth and the very special 200-off RS200 to be approved, and to go on sale as competition cars. His influence was immense, as motorsport supremo Stuart Turner recalls:

‘I lost count of the number of times Walter kept the Sierra and RS200 programmes on life-support, when we needed money, and allies. We couldn’t have brought them in without him….’

It was Hayes, too, who finally convinced Ford that they needed to back a series of new F1 engines, these being the normally-aspirated Cosworth V8s which Ayrton Senna and the young Michael Schumacher used to win so many races in the early 1990s.

Other mountains, though, were still to be climbed, and it was Hayes, more than anyone else, who urged Ford to buy up AC ( ‘that was for petty cash, really’) and Aston Martin (‘I think they deserved to survive, don’t you ?’) in the late 1980s.

Both of these buys were personally inspired by his close friendship with Henry Ford II. Henry knew about the latest AC Ace, wanted to drive one, Hayes fixed a visit for the prototype to Turville Grange – and a marriage was arranged. Not that it lasted long, though this was due to a clash of personalities, rather than poor strategy.

Buying Aston Martin, it seems, came almost on a whim. Maybe it isn’t true that Ford called Hayes one morning and asked him : ‘It’s a lovely day, what shall we do ?, to which Hayes’s supposed answer was : ‘Well, I suppose we could buy Aston Martin …. ‘ – but not a lot of analysis followed an initial impulse. before he died, HF II told Hayes :

‘It won’t change the universe, but it is the kind of thing we should be doing.’

Soon after this, Hayes was drawn into his last major motorsport project – the Escort RS Cosworth. Not that he invented it – credit for that goes to the Turner-Wheeler-Moreton-Ashcroft think-tank – but because by Ford standards it was such a crazy scheme, it needed all of his legendary persuasive powers to get it started through Ford’s byzantine approvals process.

To those who did not believe in the design, Walter would put an arm around their shoulders and remind them of all the earlier projects he had championed – and which had succeeded. To those who did not think Ford needed such a competition car, he needed only to say ‘Trust me …. ‘ And to many, if Hayes backed it, then surely it was worthwhile ?

Unfortunately for Hayes, though, his time at Ford then ran out. He didn’t want to retire – his wife, Elizabeth, wondered what on earth he would do without an office to go to – but rules were rules, and no existing Ford regulations could be further bent to let him stay on after reaching his 65th birthday.

‘I was sorry,’ he later quipped, ‘to have missed the Jaguar takeover, though….’

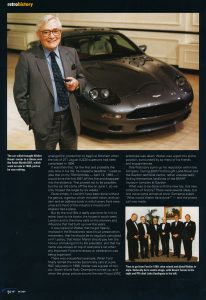

The retirement parties were many and various, the tributes were gracious and sincere – except that no-one realised how short his ‘retirement’ would be. Soon after he moved out of Ford’s HQ in Grafton Street, just round the corner from the Ritz Hotel, he was invited to join the board of directors of Aston Martin, and even that was only a temporary appointment, for his elevation to the chair then followed in 1991. Typically, his impact on that old-fashioned company was explosive. After years of havering under previous well-meaning, but short-of-finance, management, the company finally got approval to build a new and smaller car – which you now know as the DB7.

Previous bosses had talked, whinged, and built ‘paper motor cars’, but it was Hayes who did the trick. With typical, but almost unnoticed sleight-of-hand, he somehow talked Ford into marrying Jaguar XJ-S platform and power train engineering to a new XK8-related body style, had the car engineered by Tom Walkinshaw’s organisation, and then arranged for production to begin at Bloxham (near Banbury) when the last of 271 Jaguar XJ220 supercars had been completed in 1994.

It was then that, for the first and probably the only time in his life, he missed a deadline:

‘I used to joke that, on my 70th birthday, 12 April 1994, I would drive the first DB7 off the line and disappear into the distance. However, that proved not to be possible …. but the car did come off the line on 1 June, so we only missed the target by six weeks …. ‘

Quite simply, it couldn’t have been done without his genius – a genius which included vision, enthusiasm, and an address-book in which every important Ford executive and most of the industry’s movers and shakers had a place. By the mid-1990s, however, it really was time for him to retire, back to his books, his gracious house in south-west London, and to the many calls on his memory – and influence – which had built up over the years.

It was typical of the man that he got heavily involved in the Brooklands race circuit preservation movement, that he should be so regularly consulted on F1 policy, that Aston Martin should pay him the honour of making him Aston Martin’s Life President, and that his name was always on top of everyone’s list when any important Ford anniversary or celebration was being organised.

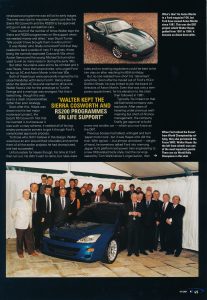

There was one perfect example. When Ford finally retired the ‘works’ Escort rally cars at a glittering pre-RAC rally party near Cheltenham in 1998, Walter was a guest of honour. Laying out the table placings did not revolve around drivers, but around Walter himself.

Seven World Rally Champions turned up to join in the fun – they had all driven Escorts at one time or another – and Walter (of course) made a gracious valedictory speech. When the group picture around the new Focus WRC prototype was taken – there’s a print facing me as I write this – Walter was urged into prime position, surrounded by so many of his friends and acquaintances. One final story sums up his reputation within the company. During 2000 Ford bought Land-Rover and the Gaydon technical centre, rather unexpectedly finding themselves landlords of the BMIHT museum complex at Gaydon. What was to be done with this new toy, this new collection of history? There were several ideas, but one move came almost at once. Some wise owl commented: ‘What would Walter have done?’ – and the phone call was made.