Secrets of the Seven. The birth of the DB7 is one of the most intriguing episodes in Aston Martin’s history. Here, key players reveal what really happened

Vantage

Autumn 2014

John Simister

courtesy and copyright of Vantage

http://vantagemag.co.uk

The Chinese call it feng shui, the auspicious alignment of lines and forces and influences that ensures a good outcome. The auspiciousness gods were certainly looking benignly on the twitching corpse that Aston Martin had almost become even after Ford had taken control in 1987, because the solution to the company’s crisis (dinosaur models, negligible sales, nothing in the future cupboard) arose from several unexpected sources.

Harry Calton joined Aston Martin as PR director in 1993, fresh from masterminding the launch of the well-received Ford Mondeo. By this time, Aston chairman Victor Gauntlett had relinquished his high-profile role and Ford persuaded Walter Hayes, marketing genius and industry grandee (the Lotus Cortina, Ford GT40 and Cosworth DFV were all conceived on his watch), out of retirement and into Gauntlett’s shoes. There had been speculation for years of a new, smaller Aston Martin, with Gauntlett talking of a project DP1999 which was little more than an imagination’s figment. Hayes was the man who actually got the idea off the ground.

But how? Where to begin? ‘After Ford bought Jaguar in 1990,’ Calton recalls, ‘there was the question of what to do with Aston. That’s when Walter came in. He talked to Tom Walkinshaw, who had been pitching to do a Jaguar XJ-S replacement. Jaguar’s Bill Hayden had knocked that on the head, so TWR and its factory at Bloxham, which had developed and built the XJ220 and various Jaguar road car conversions, were available.’

Jaguar had already abandoned its planned ‘F-type’, codenamed XJ41 (coupe) and XJ42 (convertible), after it had grown too heavy and expensive with its four-wheel drive. TWR’s lighter, cheaper alternative, Project XX, began as the XJ41 shape on an XJ-S platform, and TWR got as far as re-engineering the windscreen position and redesigning the glass areas. ‘Next thing,’ says TWR’s then-designer, Ian Callum, ‘it was suddenly a case of “not invented here’ on Jaguar’s part, because Ford decided it wanted Jaguar to develop a new car that would be cheaper and more efficient to build- the car became the XK8. So they decided not to go ahead. Tom said: “Now we need to find a client for this half-done project,” because it didn’t have to follow any particular form.’

The feng shui, was starting to align itself. Hayes and Walkinshaw each needed what the other could offer, and XX started to become Aston Martin Project NPX, for Newport Pagnell Experimental, even though Aston Martin’s Newport Pagnell operation had very little to do with it. Obviously the starting point was the existing XJ-S, but TWR re-engineered almost every part of that base. ‘A rebodied Jaguar? Not really,’ Calton reflects.

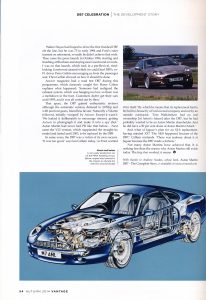

There is a notion that Callum simply Aston-ised a design intended for Jaguar, but there was more to it than that. Project NPX’s shape was designed from the start as an Aston Martin, reinterpreting some shapes and surfaces from past Astons, with just XX’s packaging and hard points as the kick-off. Callum, who had been with Ford before leaping into the heady, high-octane world of TWR, was enjoying a new design freedom and came up with a sensuous but muscular shape which, give or take a touch of residual Jaguar roundedness, was to set a tone for nearly all subsequent Astons.

As for the mechanicals, Walkinshaw envisaged using Jaguar’s V12, a unit he knew extremely well after years of racing it. Hayes, however, preferred the idea of a straight-six, partly as a link to past straight-six Astons, partly because it would be cheaper, so NPX had to be designed around this taller unit. As to which six, the most obvious choice was Jaguar’s all-aluminium AJ6 unit launched in the XJ-S and subsequently the company’s core engine.

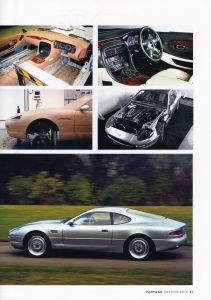

But while it fitted in the XJ-S, he AJ6 was too tall for the body Callum had created. ‘Pete Dodds, the engineering manager, asked me to raise the bonnet,’ says Ian Callum, ‘but that made it look even more like a Jaguar. Tom asked me how much we’d need to lower the engine, and I said about 25mm or 30mm. “Right, we’ll drop the engine,” said Tom, much to Pete’s annoyance because it meant they’d have to design a new subframe.’

The lowered centre of gravity would be a welcome bonus; along with new rear suspension geometry, to make the tail sit lower according to Callum’s desired stance, it would help make the new Aston Martin a better-handling car than its Jaguar platform-provider had been. ‘It was a victory for design over engineering and packaging,’ says Callum. ‘I had total autonomy over how the car would look. Tom understood that it had to look great, because people would buy it primarily for the aesthetics. The DB7 was a good car to driver; not the greatest but good enough. It was the looks that sold it.’

So, what would be the AJ6’s capacity and state of tune? The XJ41 had been intended to use a 4-litre, twin-turbo version of this engine, and indeed the first running NPX prototype was thus powered. ‘This was being developed for the X300 [revised XJ6],’ says Craig Wilson, the DB7’s chief programme engineer, ‘and it would have gone in the XJR version.’ But Walter Hayes was keen on supercharging, having been involved with it in Ford’s US Thunderbird, and favoured a similar Eaton unit for what was now called DB7, Hayes having gained permission from David Brown to reintroduce his initials.

So TWR developed an Eaton M90-supercharged version of the smaller, 3.2-lire AJ6, developing a useful 335bhp and to be built entirely by TWR at Kidlington, even down to doing its own machining of raw castings. Jaguar then copied the idea in-house for the 4-litre version of the straight-six, destined for the new XJR saloon in place of the abandoned twin-turbo. Jaguar’s version spun the supercharger more slowly and used the updated AJ16 engine development, later adopted by Aston Martin.

The first, twin-turbo DB7 prototype differed little visually from the clay model that TWR’s Kidlington studio had created, and the production car in turn barely changed from the prototype apart from losing its clamshell bonnet- it extended right down to the sills, E-type-fashion- in favour of a normal panel and front wings. Not quite normal, actually; wings, bonnet and bootlid were all glass-reinforced resin transfer mouldings, but after the first few production cars the bonnet was changed to steel to combat problems of heat distortion and too-mobile panel gaps.

Not that there would have been any production cars without Ford’s go-ahead. This is often the point at which designers and engineers have their ideas squashed by cautious management and despondency takes hold, but not here. As Harry Calton recalls: ‘They came up with the idea of doing a dynamic presentation to the management rather than a static one, and it went very well. The car drove in, it made a nice noise, and that was it.’

What Ford’s product-approval committee didn’t know, though, was that not only had the prototype been driven to the presentation at Aston Martin’s London sales office, it had already had an unofficial, and rapid, shakedown. ‘The test driver did 150mph in it before the presentation,’ Callum reveals, ‘and it had a Perspex windscreen. Not even polycarbonate, never mind glass, just Perspex heated and shaped over a buck…’

The next task was to reveal it to the press and public at the 1993 Geneva show. Harry Calton had just arrived at Aston Martin, and discovered that no press material had been prepared. ‘They hadn’t done any, and Roger Stowers [the archivist, sadly no longer with us] was processing photographic prints in his garage. We’d need several thousand for Geneva, so that wasn’t going to work. So I applied a Ford process to it, and got Ford of Europe involved too.

“We were getting a lot of support from the Newport Pagnell workforce, even though the car wasn’t going to be made there. Some of them spent all of the Friday and Saturday putting the press packs together, and then Mike Peach, one of the engine builders, drove to Geneva with them on the Sunday ready for the press day.’

Post-Geneva, the DB7 retreated from public gaze while development continued and the Bloxham factory of what was now known as Aston Martin Oxford- a company separate from Newport Pagnell- was made ready. In August 1994 the new car, in almost-production form, reappeared for a press presentation and assembly began of the first production cars. ‘Assembly’, note, not ‘manufacture’, because much of the latter was subcontracted. Motor Panels of Coventry made the bodyshell and panels, Rolls-Royce painted them, and Callow and Maddox did the trim. The paint later moved in-house to Bloxham, and Newport Pagnell’s expert but under-employed trimmers later took over the interior.

Walter Hayes had hoped to drive the first finished DB7 off the line, but he was 75 in early 1994 and Ford’s rules insisted on retirement, so sadly he didn’t achieve that wish. Then came the press launch in October 1994, starting and finishing at Bloxham and staying near Goodwood en route. I was on that launch, which took in a pre-Revival, tired-looking Goodwood around which we could hurl DB7s, ex-F1 driver Peter Gethin encouraging us from the passenger seat. Then Gethin showed us how it should be done.

Autocar magazine had a road test DB7 during this programme, which famously caught fire. Harry Calton explains what happened: ‘Someone had realigned the exhaust system, which was hanging too low, so there was a meltdown in the boot. Customers didn’t get their cars until 1995, and it was all sorted by then.’

That apart, the DB7 gained enthusiastic reviews although the automatic version, detuned to 317bhp and with just four gears, found less favour. Naturally a Volante followed, initially ‘scooped’ by Autocar. Except it wasn’t: ‘We leaked it deliberately to encourage interest, getting Autocar to photograph it and make it into a spy shot.’ Aston Martin had never had PR like that before…Next came the V12 version, which supplanted the straight-six model and lasted until 2003, to be replaced by the DB9.

In some ways, the DB7 was a victim of its own success. ‘It was too good,’ says Ian Callum today, ‘so Ford wanted it for itself.’ By which he means that its replacement had to be built in-house by a Ford-owned company and not by an outside contractor. ‘Tom Walkinshaw had no real ownership [of Aston’s future] after the DB7, but he had probably wanted to be an Aston Martin shareholder. And he did have a 50 per cent share of Aston Martin Oxford.’

And what of Jaguar’s plan for an XJ-S replacement, having rejected the XX? ‘The XK8 happened because of the DB7,’ Callum contends. ‘There was jealousy about it at Jaguar because the DB7 made a fortune.’

Not many Aston Martins have achieved that. It is nothing less than the reason why Aston Martin still exists today. The feng shui works, it seems.

With thanks to Andrew Noakes, whose book, Aston Martin DB7 – The Complete Story, is available at www.corwood.com